Integrating scientific research and biblical interpretations

I’m a scientist with 40+ years of experience in biochemistry, microbiology, molecular biology, and genomics. I believe in God, and I’m a Christian. From a church practice standpoint, I’m a Lutheran Christian. With my background in science and religion, I’m interested in integrating faith and scientific principles. Now, faith, obviously, does not require scientific proof. Indeed, strongly believing in something for which there’s no proof is the very definition of faith. Some examples of how faith is defined are:

Merriam-Webster: Firm belief in something for which there is no proof.

Cambridge Dictionary: Great trust or confidence in something or someone.

Wikipedia: In the context of religion, faith is belief in God or the doctrines or teachings of religion.

Compassion International: Biblically, faith is considered a belief and trust in God based on evidence, but without total proof.

Disclaimer: I should emphasize at the outset that I don’t know either Greek, Hebrew, or Aramaic, and I’m not exceptionally versed in the Bible’s texts. So, much of my information emanates from reading books by biblical scholars.

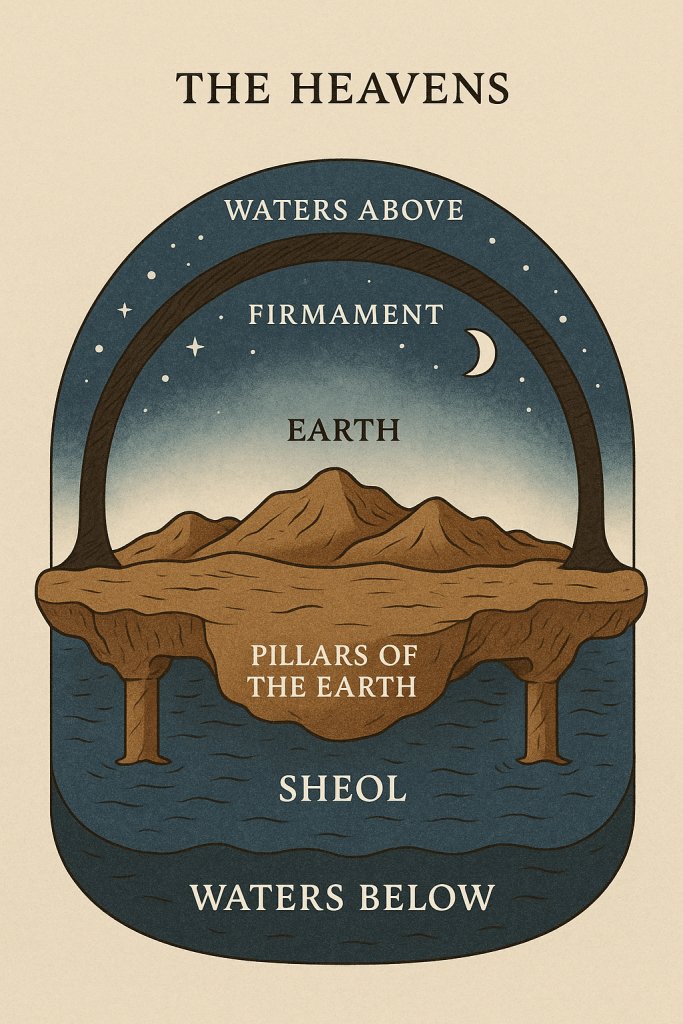

The Old Testament

Now, if faith has nothing to do with scientific proof, why on Earth am I interested in combining the two? Well, I didn’t say I’m looking for scientific proof of faith; I’m more in the search for making scientific sense of faith-related questions. For example, when looking for scientific explanations of texts in the Book of Genesis, the first book in the Christian Old Testament and the Hebrew Bible, it’s important to realize that although Genesis was written for us, it was not written to us; it was written to the Israelites to be understood in a culture some thousand years ago. To whomever God was communicating with, the purpose was not to teach cosmology. It didn’t make sense for God to tell the folks of that time that the Earth was round, rotated around the sun, moved through space, that the sun was farther away than the moon, or that the sky was not solid and held back a body of water. God used a language and a knowledge base that could be appreciated by the intended audience. For example, the Israelites of the time believed in a firmament that separated the Earth from an “upstairs” body of water. This explained rain (water coming down from above).

So, when Genesis 1 implies that God made the Earth and the rest of the universe in six days, what gives? Well, one interpretation, of course, is that God created everything in six 24-hour days. That view is difficult to reconcile with the fact that the universe as we know it and the Earth are 13.8 and 4.5 billion years old, respectively. Another possibility is that six days refer to periods of several million years each. The problem here, according to biblical scholars, is that the way the Hebrew word for day (yom) is used in the Scripture seems to indicate a 24-hour day. Additionally, the presence of “evening and morning” with the first six days argues against long periods of time.

A third option is a literary (not literal) view, in which the author of Genesis uses a regular week as a framework or analogy to describe creation. The actual timeframe is not prioritized. This view also bypasses some of the chronological inconsistencies in Genesis: for example, darkness and light are separated on the first day, but the sun, moon, and stars are not created until the fourth day. This makes sense to me.

A fourth alternative proposed by John Walton [1] interprets the use of the Hebrew word for create (bārāʾ) in Genesis 1 as a functional ontology rather than a materialistic one. Thus, in six days, God functionalized the already-formed Earth by naming, separating, and assigning functions and roles to the system. An interesting notion.

So, if the Earth was already there, where did it come from? The first verse in Genesis 1 reads: In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. In Hebrews 11:3 in the New Testament, we find the statement: By faith, we understand that the universe was created by the word of God, so that what is seen was not made out of things that are visible. Creation ex nihilo, out of nothing, also seems to imply a non-materialistic term for the creation process and may be in line with the cosmological Big Bang theory.

Who wrote Genesis? It’s been accredited to Moses, but it’s more likely a compilation by several authors (possibly including Moses) of ancient literature and oral traditions, including those from ancient Near-East civilizations. Chapters in Genesis share striking motifs, imagery, and even structure with several older Mesopotamian and Near-Eastern texts, some of which predate the Hebrew Bible by more than a thousand years. For example, the creation narrative shows parallels with the Babylonian myth Enuma Elish: it begins with watery chaos, a separation of waters above and below, the creation of a firmament or sky dome, and ends with a divine rest. The story of Noah and the ark appears to be borrowed in part from the Epic of Gilgamesh, a Mesopotamian tale [2, 3], and the Tower of Babel story draws from older Mesopotamian traditions [4].

As regards Adam and Eve, two other prominent figures in Genesis, also here, there are older Near-Eastern and Mesopotamian precedents that resemble the Adam and Eve story in several key themes: human creation from clay, divine breath or life force, forbidden knowledge, paradise-like gardens, and loss of immortality through disobedience or trickery [5].

While none of these stories is a direct source for Genesis 2–3, they all helped shape the ancient setting that inspired it. The Hebrew version takes those old myths and gives them a new twist—turning them into a story about one God and moral choice. In other words, it seems likely that Genesis reworks older themes within a monotheistic and ethical framework rather than a polytheistic one. I think this difference between the monotheistic nature of the Old Testament and the polytheistic belief system of other ancient texts is significant.

I find it possible that God intervened in human evolution at some point in the distant past and physically visited Earth to make a covenant with mankind, explaining how humans should behave as stewards of the Earth and of one another.

Exodus is described in Book 2 of the Old Testament. The literary shape of the Exodus story seems to reflect mythic patterns already known centuries before the biblical version — in Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Canaanite literature. Such parallels include: a baby placed in a reed basket, sealed with bitumen, set adrift on a river; rescued by someone of higher status; crossing seas or dividing waters [2, 3].

I believe that various ancient works, including Near Eastern and Mesopotamian texts and the Old Testament, aim to describe—starting with oral traditions and later in written form—how God created the Earth and the Universe(s).

On a related note, how did life start on Earth around 4.3 billion years ago? One possibility is that it occurred purely through abiogenesis. Another option is that life was kick-started on the planet by seeding it with cells.

The New Testament

Let’s turn to the New Testament. Since I’m a Christian, I believe that Jesus came to Earth from/as God. I subscribe to the Trinity concept; i.e., that God exists as three equal entities: the Father, the Son (Jesus), and the Holy Spirit. As I understand it, Jesus never used the exact words I am God, but he spoke and acted as if he was, and that’s why his enemies accused him of blasphemy and his followers worshiped him as Lord.

I find it interesting to consider what might have happened if Emperor Constantine (the Great) had not been victorious at the Council of Nicaea (AD 325). Constantine was not a theologian; he was a politician, a military strategist, and a new Christian convert trying to keep a vast and unstable Roman Empire together. Although early Christians spoke of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit acting together, there was no single, universally agreed-upon way to define this relationship. Some viewed Jesus as fully divine, while others—most notably, the priest Arius—believed Jesus was created by God. This disagreement threatened the unity and peace of the rapidly growing church and the entire Empire. Eager to promote religious unity and political stability, Constantine called a council at Nicaea with around 300 bishops to settle the issue. In the council’s decision, known as the Nicene Creed (fully reaffirmed at the Council of Constantinople some decades later), Constantine established the doctrine of the Trinity — that Jesus, God, and the Holy Spirit are one and the same.

So, essentially, the Nicene Creed, which became imperial law, was politically motivated to stabilize the Roman Empire. If Constantine had failed to unite the bishops at the Council in Nicaea, the consequences would likely have been both dramatic and far-reaching, affecting theology and politics alike. Possibly, the Church could have developed into multiple rival theologies, with the Trinity remaining a minority doctrine rather than becoming the core of Catholic (universal) Christian orthodoxy. However, it’s also possible that the views of early Christians—who didn’t have a technical doctrine to fall back on, but worshiped the Son, the Father, and the Holy Spirit together—would have matured to encapsulate the Trinity regardless of the outcome of the Nicene Council.

The question of whether there was a historical Jesus (a real person who lived in 1st-century Judea and became the nucleus of the Christian movement) has been investigated by believers, skeptics, and secular historians for over a century. The vast majority of historians (including non-Christians) agree that Jesus existed historically. For example, the crucifixion under Pontius Pilate is considered one of the best-attested facts in ancient history, recorded by all four Gospels, Paul’s letters, and non-biblical sources by the Jewish historian Josephus (circa 93 AD), the Roman historian Tacitus (circa 116 AD), Pliny the Younger, a Roman lawyer and writer (circa 112 AD), and Suetonius, a Roman historian (circa 120 AD).

Bart Ehrman, an agnostic and strong critic of Christianity, is one of the most prominent biblical scholars of today. In his book Did Jesus Exist? [6] Ehrman concludes that Jesus of Nazareth was unquestionably a real historical person because the evidence for his existence meets the same standards used for any ancient figure: multiple early, independent sources (especially Paul’s letters written within decades of Jesus’ death), references to Jesus’ family and execution under Pilate, and the implausibility of inventing a crucified Jewish messiah, which no one in that culture would have fabricated. Ehrman argues that the simplest, historically coherent explanation for the rise of the Christian movement is that it began around an actual 1st-century Jewish teacher whose life and death inspired later theological developments.

Accepting Jesus as a historical person seems like a no-brainer. Having done that, the next question is: who was Jesus, a prophet, apocalyptic preacher, messianic reformer, or divine being? C. S. Lewis famously stated that either Jesus was a complete nutcase or he was and is divine: “…but let us not come with any patronizing nonsense about his being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us.“ [7]. A version of Lewis’ trilemma can also be found in his book The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe [8].

So, who did Jesus say he was? Well, most historians and biblical scholars agree that Jesus understood himself as God’s chosen and authorized agent. He called himself the Son of Man and, although he didn’t explicitly claim to be the Messiah, he accepted that role, spoke of God as his unique Father, and claimed divine authority to teach, forgive, and judge.

How about the miracles attributed to Jesus, including his own resurrection? First off, there were other Jewish and Greco-Roman figures around the time of Jesus (1st century BC) who are reported to have claimed or been attributed miracles. However, what stands out about Jesus is the resurrection claims. What seems all but unanimous among biblical scholars—including skeptics like Bart Ehrman—is that some disciples had powerful experiences they interpreted as seeing Jesus alive, that these experiences were both individual and group events, and that they sparked the rapid rise of the early Christian movement centered on resurrection faith. [6, 9]. What is debated is the nature of these experiences—physical encounters, visions, or spiritual experiences—and how many witnessed them.

One of the most compelling arguments for accepting that the disciples were convinced that Jesus rose from the dead is that they were prepared to be tortured and martyred for their faith. Many of the accounts describing the deaths of the disciples date from the 2nd century onward and likely include legendary embellishments. However, there are early sources (Christian and non-Christian) that show some Christians, including followers of Jesus, were persecuted in the first and second centuries. For example, the Christian writer Clement of Rome (c. 95 AD) refers to Peter and Paul having endured martyrdom [10]. Another of Jesus’ followers, James the son of Zebedee, is explicitly stated in the New Testament (Acts 12:1-2) to have been put to death by Herod Agrippa, which qualifies as martyrdom in the broad sense. So, I think it’s fair to say that the idea that some disciples died for their faith is very likely.

I hope this rather lengthy treatise is of interest to others, but mostly I wrote it for myself, to organize my thoughts. With the risk of coming across as pretentious, I’d like to posit that I aim for a grounded, rather than blind faith—faith in which I try to gather available facts, or at least statements based on sound reasoning—and then decide what I believe. I would argue that this sentiment also applies to the political arena. It’s convenient to take at face value what you read or hear from your support orbit without taking the time to look up sources and form your own unbiased opinion.

References

[1] The Lost World of Genesis 1 (2010) Walton, J.

[2] Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, …, (2009) Dalley, S..

[3] Old Testament Parallels: Laws and Stories from the Ancient Near East (2023), Matthews, V. H….

[4] Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament (2006) Walton, J.

[6] Mesopotamian Mythology and Genesis 1–11 (2023), Klamm, K. and Winitzer, A.

[6] Did Jesus Exist? (2013) Ehrman, B. D.

[7] Mere Christianity (1952) Lewis C.S.

[8] The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (1950) Lewis, C. S.

[9] The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus (2004) Habermass, G. R.

[10] Did the Apostles Really Die as Martyrs for their Faith? (2013) McDowel, S.